Cycles of Life and Learning in the Living Classroom

By Natalie Berkman and Holly Conn

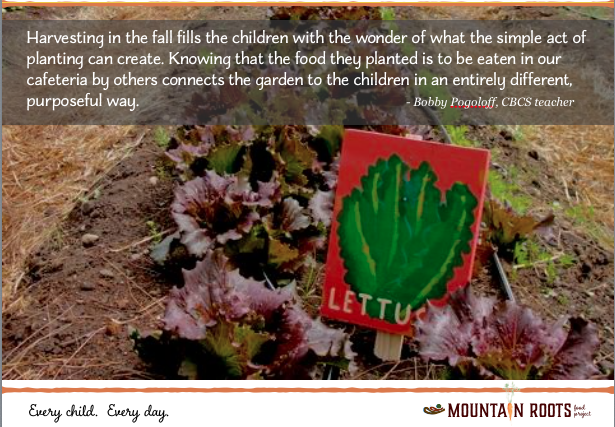

Spring: Farm field trips, guest chefs, and seed starts. As the world wakes up from winter sleep, Mountain Roots gets kids ready and excited for the upcoming growing season. “The planting of seeds in the classroom and planting of starters in garden in spring is really powerful. The kids become so connected to the success of those plants,” explains CBCS teacher Bobby Pogoloff.

Instead of reading about how seeds grow, and looking at diagrams in a book, kids are planting tiny seeds, warming them in lighted carts they call ‘grow labs,’ and watering, observing, and even measuring them daily until the ground is warm enough to transfer them out to the garden. “Our class planted the whole first row,” says Maggie Whiting, 9. “It’s broccoli, and kale, and I think cabbage. It was amazing to see how fast they grew. We’re going to eat them in the fall,” she says, “when I’m in fourth grade.”

Seed starting is just one of many hands-on experiences kids are getting as the garden, and other Farm to School education, is integrated into curriculum. Hands-on learning provides kids with experiences that a traditional classroom lesson doesn’t. In Gunnison and Crested Butte, the school gardens provide a venue that K-12 teachers can use to enrich the learning process. Sometimes called ‘experiential,’ or ‘place-based’ learning, the effectiveness of hands-on learning to advance 21st century education is now widely recognized and schools are seeking ways to implement it into curriculum.

In the traditional classroom, children primarily use attention and memory to learn. Experiential learning is touted for developing critical-thinking skills, a deeper understanding of the material, and the ability to make connections between what they’re learning in the classroom with their lives and the world outside of the classroom. In addition, school gardens allow children to develop life skills in areas such as nutrition, leadership, and decision making. Perhaps even more relevant today is the opportunity that gardening gives children to reconnect with nature. Research and anecdotal evidence tells us that when this connection with our natural world is established and nurtured, the child’s mind becomes centered and focused, eager to attack other areas of academia.

Mountain Roots installed the garden at Crested Butte Community School in 2011, and each year more relationships with teachers are built and more opportunities for classes to use the garden as a ‘Living Classroom’ are provided. But teachers are already so overwhelmed with demands on their time — due to a number of factors, including standardized testing and educational standards outlined by Common Core and Next Generation — that to implement garden-based learning in a meaningful way, teachers knew it was essential to align experiential learning with those standards.

So Mountain Roots is making an investment in environmental education. The organization hired four environmental educators and is now working with specific grade levels (K,1,3,and 7) in both Gunnison and Crested Butte on a three-year pilot program to design and teach select units in science and health that directly align with the state standards. “We started planning the pilot program when we applied for a big education grant out of Boston,” Executive Director Holly Conn says, “We didn’t get it. But the project was outlined, and the schools were excited about it, so we decided to see what we could do on our own, with community support.”

It’s a response to requests from teachers and administrators, but also timed with the release of the Colorado Environmental Education Plan (CEEP), that outlines a coordinated strategy between PreK-12 teachers, environmental education providers, and leaders in Colorado to restore and increase field experiences as part of the school curriculum.

“We are in touch with the teacher ahead of time. We research their standards, we find out what they’re working on, we create a lesson around that, and then we go outdoors with the teacher and the class, “ says Jenny Whitacre, who leads the Mountain Roots environmental education team. This strategy works well in fall, when the garden is thriving, and for spring planting. “Well, Crested Butte’s spring is really still winter,” she laughs, “so we bring the experiences in, with the guest chefs and grow labs.”

SUMMER in the garden means cultivation. In Roots & Shoots: Summer Field Studies camps, local and visiting kids spend mornings in the garden, tending the soil and plants, observing growth, and becoming attuned to the ecosystem they created in the garden. Camper Maya Conn,9, shares, “My favorite part of the garden is being part of all the little creatures and bugs and mice and snakes and birds.” Afternoon field trips to forests, rivers, farms, and local kitchens connect them to the wider ecosystem of the Gunnison Valley. As food ripens, kids harvest, cook, bake, can, and pickle, run a farm stand, and prepare donation boxes for people in need.

By participating the process of growing food, students have an informed approach to eating without an official lesson in “healthy eating.” For many K-12 students, working in a school garden is the first time they are making a real-life connection between the items they see in the grocery store and their original location. “The kids were so excited to harvest the vegetables and then make pickles and jam – to do everything from scratch,” says Mountain Roots’ youth educator Sasha Legere. “They love that it’s all homemade.” Healthy eating is one of the most obvious lessons taught in the summer programs, but teaching about connections — the relationship people have with their food, and the impacts food choices have on the economy, the environment, connections is important, too. “We harvested for Backyard Harvest (a fresh food donation program) and it taught the kids about community and that there are people in our community that can’t afford or don’t have access to fresh, local food. And we taught why it’s important.” Camper Lhotse Wycoff, 11, explains, “Some people can’t afford fresh food – they just go to McDonald’s because it’s cheap. We want them to have fresh grown foods. We get to help them.”

AUTUMN: Now that school is back in session, students harvest the garden’s bounty for the school cafeteria, and kids enjoy the delicious evidence of the hard work they’ve put in all season. As part of the new pilot program, as many as 18 classes will visit the garden for core academics in science and health with a 21st century twist. Tacked to fridges and walls, Harvest of the Month menus help to bring the education into the family. The colorful menus feature a regional produce item each month along with nutrition information and a physical activity topic of the month.

One project in particular stands out from the rest: the Sensory Garden at CBCS. A sensory garden provides an intimate space that invites children to experience plants and natural spaces through all five senses. With specially selected plants and design elements, like wind chimes, fluttering silks, or water features, a sensory garden immerses visitors in fragrances, sounds, colors, textures, and movement. Sensory gardens are designed with children and adults with special needs in mind, but are loved and used by all. They can be relaxing and therapeutic, enhance creativity, and can help support concepts and curriculum taught in the classrooms. This fall, professionals Margaret Loperfido of Sprout Studios and Bart Laemell of B3 Builders will be working with a junior-senior level Civil Engineering class to design the Sensory Garden. Students will learn the principles of design, about alternative and therapeutic classroom settings, and Autocad software. Then they’ll apply these skills to create team designs, and the best of the best will be selected for installation. The first phase of installation is scheduled for fall break (October 2015).

Mary Thomas, a reading recovery specialist in California, has experienced the benefits of her school’s sensory garden many times over. “Before our sessions I walk with each of my students through the garden. We smell fragrant herbs and feel the fuzzy lamb’s ear or the silkiness of a chestnut,” Thomas says. “These short walks relax the students and help them to focus. There is no question that it helps them perform better in our academic sessions. The garden calms them, and me, as if to say ‘it’s okay, keep at it and you will get it. Everything blooms in its own time.’ ”

Secondary science teacher Renee Brekke Ebbott will be working with Mountain Roots on ecology lessons for Life Science classes and an Environmental Science elective. “I am so excited to incorporate the school garden into my curriculum! We took a tour of the garden on the first week of school and I was so energized by the excitement and conversation the garden created, “ she shares. “Just last week, I watched a student that struggles in the classroom excel during our first lesson outside. It was a joy to see this student become the leader and the one with the knowledge that other students admired.”

Teachers ‘dig’ Farm to School, it seems, because garden-based learning has something to contribute to every learning style, and to children at all developmental levels. Study after study confirms that when kids have a personal experience with the subject matter, they come away from that experience with a deeper understanding of the material, and it stays with them longer. “For every teacher, it’s when you see that spark. You see eyes wide with excitement of discovery. You see connections being made,” says kindergarten teacher Kelly Piccaro. “I think that when students have the opportunities to interact with nature, they have more appreciation for the environment. Year after year, students learn the cycles of the natural world, including plant and animal life, and gain skills they can utilize throughout their lives.”