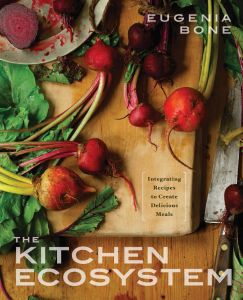

This month the Colorado Farm & Food Alliance is honored to feature award-winning food journalist and author Eugenia Bone, who writes about life in western Colorado and the efforts of the community there to protect a rural way-of-life and a growing food economy from ill-advised oil and gas leasing and development. For more on the author please visit EugeniaBone.com, read her brief biographical sketch below, and follow her blog at kitchenecosystem.com. – COFFA

When I told friends in New York that my husband and I had bought a ranch in Colorado, I was surprised to discover how many had fantasized about living out west. I didn’t realize that even the most citified among them had willingly repaired fences at guest ranches, donned heavy backpacks and dreamt of big spaces and blue mountains and long afternoons sitting on a porch.

Because I never did.

I was perfectly happy with our life in New York and its surrounding seashores, and our occasional trips abroad. But my husband Kevin wasn’t. It had been coming on for a few years: He suffered from a kind of yearning without name, a desire he couldn’t articulate, a lack of vigor and contentment that would have been mopey in a lesser man. There was, quite simply, an empty place in him that was not being filled; not by our marriage, not by our family, not by his work as an architect and professor. As this was clearly not a problem I could solve, I encouraged him to go figure it out for himself.

And so began the year of adventure weekends. Kevin went on ski trips with childhood friends, all of whom had blown out knees or messed up shoulders but braved the slopes anyway, fueled by courage and painkillers. He went on grueling backpack trips and returned with pockets full of pine needles, and yet, a few days after he was home, his discontent would resurface again. It was frustrating for both of us. But everything changed after he went on a fishing trip to the North Fork Valley on Colorado’s Western Slope, because there Kevin found his joy.

He came home and announced that he wanted to buy land in the valley. He went on and on about its beauty, the orchards, the farms, the ranches, the rivers. You go for it, honey, I said. I’m with you all the way. I didn’t worry over whether he actually would go for it. But he did. Within six months he had picked out a piece of land and put together the financing. His melancholy began to slip away–at about the same rate as my panic rose. But what was I to do? I agreed to buy a 45-acre ranch sight unseen. I signed those mortgage papers the same way I would sign a release for Kevin to have necessary surgery: it had to be done.

Kevin is from Colorado Springs, and I guess what he didn’t realize was he wanted to go home to the Rocky Mountains. After we bought the place in November 1998, there was a six-month period during which Kevin discouraged me from visiting the ranch. It seems there was a problem with exploded toilets, big rig oil spills, and mounds of rotting carcasses left over from years of poaching. There were skunks living under the house and pack rats living in the ceiling and the place stank of them all. There were plenty more problems too, but Kevin didn’t share them with me. He was, during the early renovation process, rather evasive on the subject of the ranch’s condition.

Kevin is from Colorado Springs, and I guess what he didn’t realize was he wanted to go home to the Rocky Mountains. After we bought the place in November 1998, there was a six-month period during which Kevin discouraged me from visiting the ranch. It seems there was a problem with exploded toilets, big rig oil spills, and mounds of rotting carcasses left over from years of poaching. There were skunks living under the house and pack rats living in the ceiling and the place stank of them all. There were plenty more problems too, but Kevin didn’t share them with me. He was, during the early renovation process, rather evasive on the subject of the ranch’s condition.

In the meantime, I worried about this mysterious place I would have to call home. I worried my children would be run down by mountain lions, mauled by grizzly bears, surprised by rattlers. Was I going to be stranded, miles from hospitals, fire houses, and the Gap? And what would I do for company? What, after all, did I have in common with cattlemen? And what was an Italian girl like me going to eat? Would I be able to find imported pasta? Tuna fish packed in oil? Basil?

Even though I had never seen the valley, Kevin was betting that I would be fascinated by its rich agriculture. Beginning in July, the North Fork region and its associated townships start pumping out magnificent fruits and vegetables: cherries, apricots, peaches, plums, pears, and apples; the best cantaloupes, cucumbers, tomatoes; and peppers of all kinds, which you can buy by the crate and have roasted in a metal rotisserie. The Olathe sweet corn is world-renowned; the elk, deer, beef, bison, and lamb sublime; eggs are fresh daily; local goat herders make a variety of goat cheeses; and wild chukar partridge, pheasant, and ducks are plentiful, as are the trout of the Gunnison River and its feeder streams. If there’s enough rain, mushrooms like boletes and chanterelles grow in such quantities that folks pack them out of the woods on horseback.

Kevin was right. Over the fifteen years we’ve had our place in Crawford I became increasingly attached to the North Fork Valley’s unique beauty, food culture, and independent-minded citizens, and more and more committed to the place. My friend Pam Bliss once said the longer you are in a place, the more hectic it gets, and she’s right.

Kevin was right. Over the fifteen years we’ve had our place in Crawford I became increasingly attached to the North Fork Valley’s unique beauty, food culture, and independent-minded citizens, and more and more committed to the place. My friend Pam Bliss once said the longer you are in a place, the more hectic it gets, and she’s right.

I got involved with a range of non-profits, from our groovy local radio station, KVNF and her sister station over McClure’s Pass, KDNK, to various libraries, hospitals, schools, environmental groups including the Citizens for a Healthy Community (CHC), farm groups, and local political battles. If someone asked me to donate a dinner or a book, or do a reading or a demo, I did it. Certainly a friend, but even if an acquaintance said they were curious about the region, I offered the bunkhouse as a base for their explorations. We threw semiannual pig roasts for everyone we knew, and all their family, and all their Colorado company. I founded a Slow Food convivium, and we organized dinners and farm tours to show off the local producers. My journals contained less description of the wind and hummingbirds, and more To Do lists. I even started to think of my winters in New York as time off.

In many ways the valley hasn’t changed over the years. It carries on in its own timeless time, connected to the world enough to be hip, isolated enough to be quirky. You can still admire the wit of the Crawford church sign. One hot July the sign read, “We’re prayer conditioned.” Another time, “Sign broken, message inside.” The liquor store continues to sport strange pricing, so that the dollar amount rounds out when the tax is added, but it doesn’t. When the county did a road renovation project through the adobe lands and ran out of “ Men Working” signs they put up “Bridge Out” signs instead. Folks still fill the stands at the Delta County Fair, to applaud the rodeo princesses in their tiara-adorned cowgirl hats, and to cheer the battered vehicles in the demolition derby.

In many ways the valley hasn’t changed over the years. It carries on in its own timeless time, connected to the world enough to be hip, isolated enough to be quirky. You can still admire the wit of the Crawford church sign. One hot July the sign read, “We’re prayer conditioned.” Another time, “Sign broken, message inside.” The liquor store continues to sport strange pricing, so that the dollar amount rounds out when the tax is added, but it doesn’t. When the county did a road renovation project through the adobe lands and ran out of “ Men Working” signs they put up “Bridge Out” signs instead. Folks still fill the stands at the Delta County Fair, to applaud the rodeo princesses in their tiara-adorned cowgirl hats, and to cheer the battered vehicles in the demolition derby.

“Burning gas, popping tires, and bending sheet metal,” says the announcer on a crackling PA system. “It doesn’t get any better than this.”

Over the years businesses have come and gone. A Pilates studio in Hotchkiss has opened and the farm trucks drive by the large windows real slow when class is in session. There is a local arts and crafts gallery in town, and a café that sells a chili quiche soft and light as a soufflé, and Texas brownies dense as a dictionary. And there are more farms! Not just more those I’ve newly learned about, though that too, but new ventures that speak to the future of the valley. New vineyards, a distillery, B&Bs, a gorgeous lavender farm, cheesemakers, a cider concern that was bought by a young couple and transformed into an orchard store-wine tasting room-knitting supply shop-deli that has become a community destination. Linda and Marley Hodgson restored the Smith Fork Ranch, once the dumpiest in the valley, into a sumptuous guest ranch that employed just about every artisan around for years.

Slow Food groups from elsewhere in Colorado started to notice us, and restaurants from the tonier parts of the state began to prize the valley products they featured on their localvore menus. While there aren’t many restaurants in the valley, wine dinners and farm dinners have become a regular part of the social calendar, and our own Slow Food Western Slope, which has expanded in size and ambition, launched campaigns to bring local foods into the school cafeterias, among many other worthy efforts. The dining/performance art troupe Outstanding in the Field conducted a couple of dinners at Zephyros Farm and Gardens, and then the owners, Don and Daphne, started organizing their own boisterous dinners, like the Farm Funk Party where we danced in a dark stubbly field while children explored the banks of a black pond with flashlights, and the No Cash Farm Bash, a community wide pot luck that revealed to me how many young families were making a life here.

Slow Food groups from elsewhere in Colorado started to notice us, and restaurants from the tonier parts of the state began to prize the valley products they featured on their localvore menus. While there aren’t many restaurants in the valley, wine dinners and farm dinners have become a regular part of the social calendar, and our own Slow Food Western Slope, which has expanded in size and ambition, launched campaigns to bring local foods into the school cafeterias, among many other worthy efforts. The dining/performance art troupe Outstanding in the Field conducted a couple of dinners at Zephyros Farm and Gardens, and then the owners, Don and Daphne, started organizing their own boisterous dinners, like the Farm Funk Party where we danced in a dark stubbly field while children explored the banks of a black pond with flashlights, and the No Cash Farm Bash, a community wide pot luck that revealed to me how many young families were making a life here.

Food and community go hand in hand. I helped John Cooley of Rivendell Farms dig his lovely, aromatic potatoes (“Aren’t they just beautiful?” he’d gush over every cluster of spuds), I helped Elsie and Sven braid their powerful purple haze garlic, salted Hungarian hot peppers with Kathryn, made mulberry mead with Michael, prepared country pate with Yvon, canned cases of tomatoes with Candy, and went mushroom hunting with Linda. Every summer I make new friends, learn about their farms, and cook with them and write about them so the whole nation will know what a very, very special place the North Fork Valley is.

But something else has happened, too. An insidious creep of industrial greed appeared in our community. At first, we only heard rumors about frackers who’d set their sites on the patchwork of BLM properties between the organic farms, but soon it was clear that extraction companies were on the scent, but with no sense of what the valley had going on. They bid to build roads and drill pads and container ponds based on geological maps void of people or businesses or farms or schools. There were bids to frack the Paonia reservoir dam. Bids to frack an avalanche on the side of Mount Lamborn, a bid to frack a lot so close to the high school that if a kid hit a homerun in a baseball game he’d likely hit a drilling rig. Farmers who didn’t own their mineral rights were looking at the industrialization of their organic farms, and questions of water safety, road maintenance, and air pollution, all of which would impact the businesses thriving in the valley, were brushed aside by a battery of lawyers and their friends in government. Local people were told fracking would bring jobs, but not told most of the well-paying jobs would be imported, and the real jobs would end up being pollution clean up. The natural gas industry was on a collision course with the agricultural future of the valley. It seemed like just when the valley was really getting known for its wonderful agriculture, and attracting smart, vital young people to the area to start farming, winemaking, and animal husbandry, competition for the rights to its future had begun.

But the natural gas folks underestimated the will of the valley people and their ability to mobilize. Public meetings were swamped with concerned—and very vocal—citizens. I took a train from New York to join a group of North Fork business owners to visit the BLM big shots in DC, and to educate Colorado’s congressmen and senators about just what was at stake. It was not easy. The natural gas industry is very rich, very powerful, very influential. But the people of the North Fork Valley had the moral high ground and for the time being, the BLM has listened and the bristling entitlement of the natural gas industry has backed down. They will stay quiet, for now, because gas prices are depressed, but gas will become costly again, and then the industry will return, willfully ignorant of the sustainable businesses in the valley, backed by their powerful friends.

As so many places that face this issue, the designs of the oil and gas industry will remain a threat to the valley until the community itself decides its own future.

I know it can be disheartening to have to keep fighting the same battles over, but each win is actually progress. For now, the North Fork has shown that rural communities can stand up to powerful interests. But we can’t relax our efforts until the threat of industrialization is gone. It’s a long haul, but like all endeavors where citizens must fight for their rights in the face of entrenched privilege, our fortitude and our unity, and our love of home will, in the end, prevail.

Eugenia Bone is a nationally known food journalist and author. Her work has appeared in many magazines and newspapers, including Saveur, Food & Wine, Gourmet, Fine Dining, Martha Stewart Living, Wine Enthusiast, Sunset, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and The Denver Post.She is the author of five books. At Mesa’s Edge was nominated for a Colorado Book Award. She wrote Italian Family Dining with her father, celebrated chef Edward Giobbi. Well-Preserved was nominated for a James Beard award, and was on many best cookbooks of 2009 lists. Mycophilia: Revelations From the Weird World of Mushrooms, was on Amazon’s best science books of 2011 list and nominated for a Council on Botanical and Horticultural Libraries award.

Eugenia Bone is a nationally known food journalist and author. Her work has appeared in many magazines and newspapers, including Saveur, Food & Wine, Gourmet, Fine Dining, Martha Stewart Living, Wine Enthusiast, Sunset, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and The Denver Post.She is the author of five books. At Mesa’s Edge was nominated for a Colorado Book Award. She wrote Italian Family Dining with her father, celebrated chef Edward Giobbi. Well-Preserved was nominated for a James Beard award, and was on many best cookbooks of 2009 lists. Mycophilia: Revelations From the Weird World of Mushrooms, was on Amazon’s best science books of 2011 list and nominated for a Council on Botanical and Horticultural Libraries award.

Her fifth book, The Kitchen Ecosystem (October, 2014) has been nominated for a Books for a Better Life award, and was on many best cookbooks of 2014 lists. Her writing and recipes have been anthologized in a number of publications, including Best Food Writing, Saveur Cooks, and The Food & Wine Cookbook, among others. Eugenia has lectured widely, in venues like the Denver Botanical Garden and the New York Pubic Library, judged food and wine competitions, and she has appeared on television and radio many times.

She is the founder of Slow Food Western Slope in Colorado and the president of the New York Mycological Society, which was founded 50 years ago by composer John Cage.

She writes the blog, kitchenecosystem.com. Eugenia lives in New York City and Western Colorado. Contact Eugenia through her website, eugeniabone.com, facebook page Eugenia Bone Books or follow her on twitter @eugeniabone